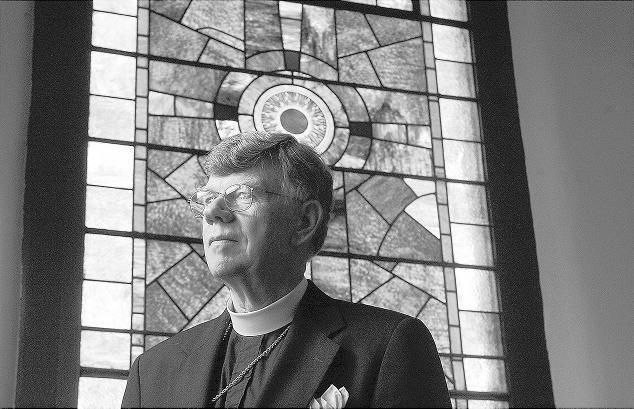

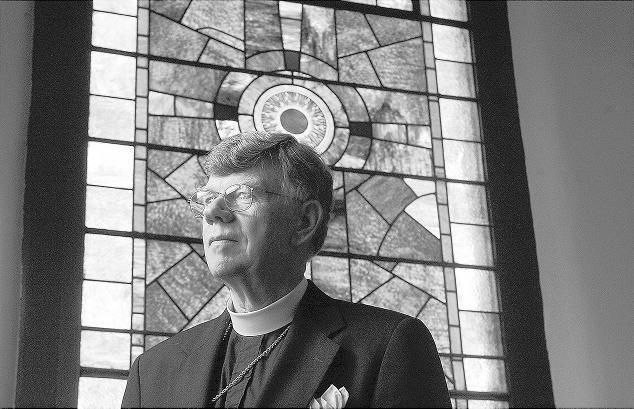

Free Lance-Star, Posted: Sunday, May 4, 2003 1:08 am By JANET MARSHALL

NEAR THE END of his farewell sermon last Sunday, the Rev. Charles Sydnor of St. George’s Episcopal Church said he had one last, important thing to pass on.

For nearly 30 years, Sydnor had tended to the spiritual needs of his parishioners, baptizing their children, counseling them through adversity and challenging them to reach out to those in need.

He had been there in less lofty times, too, tending to mundane chores such as unlocking the church doors when someone needed to get in.

And so, as Sydnor wound down his sermon, he held in his hand an important part of his downtown Fredericksburg ministry: the master key to the building. He was ready to pass it on.

“Now I’ll be able to say, ‘I’m very sorry you can’t get in, but let me refer you to someone else. I’ve retired and I don’t have the key,'” Sydnor said, grinning.

For those who have worshipped at St. George’s and those who have been touched by the causes Sydnor has championed, it’s hard to imagine the church without him.

His extraordinarily long tenure in a time when ministers typically don’t stay in one church so long was matched by his extraordinary success at making St. George’s a force for social good.

Hope House, the Thurman Brisben Homeless Shelter, Hospice Support Care–all trace their roots to Sydnor and St. George’s.

“Everywhere there is community action, it seems you see Charles Sydnor’s name all over it,” said parishioner Trip Wiggins, the church’s volunteer archivist.

The 59-year-old rector built a reputation as an advocate for racial equality, acceptance of gays in church and anyone he considered an underdog. He opened St. George’s to community discussions on topics such as AIDS, school shootings and the wars in Iraq.

The Rev. Lawrence Davies, Fredericksburg’s former mayor, said Sydnor inspired countless charitable acts over the decades–by people from many churches, but especially St. George’s.

“It would have been easy enough for the congregation to say, ‘We do our religious thing and that’s all we’re responsible for,'” said Davies, pastor of Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site). “But they sought, under his leadership, to make a difference. And they have made a difference in countless lives in this community.”

Now, Sydnor is focused on making a difference in the life of the person most dear to him: his wife.

‘Her cheerleader, her coach’

A little more than two years ago, Maureen Sydnor suffered a nearly fatal brain aneurysm. Her lingering disabilities make it necessary for her to have full-time care.

Sydnor has paid people to help care for her. But that’s costly. And he’s certain his presence is critical to her continued improvement.

“I’m her cheerleader and her coach, and things are different when I’m around,” Sydnor said. “We have been truly blessed to laugh about what we can’t do and move forward.”

Sydnor has done an admirable job of juggling church duties with his ministry of love at home, said longtime parishioner George Van Sant, a former City Council member.

“It’s just miraculous what he’s done,” Van Sant said.

But Sydnor said he can’t fully serve the church or his wife when he tries to be there for both. So he is leaving St. George’s in the hands of associate rector Nathan Ferrell for now–and later, of whoever is chosen as the full-time rector.

“St. George’s has a wonderful future ahead, and it deserves more energy and time than I could focus on given my commitment to family,” Sydnor said.

Welcome to worship

In 1992, St. George’s hosted a World AIDS Day observance in Fredericksburg. Afterward, at a candlelight walk downtown, a man confronted participants and called them “fruitcakes.”

It was that kind of attitude that led Sydnor to host the event at St. George’s.

“Some people were saying that AIDS was God’s punishment [for homosexuality],” Sydnor said. “And I wanted to be sure we were not giving that message.”

During the vigil, Sydnor said, he told the crowd that all in attendance were welcome to worship at St. George’s.

“And ‘all’ meant ‘all,'” Sydnor said.

He wanted the doors shut to no one.

Several years later, Sydnor attended a service in a small Episcopal church in Philadelphia. Two men sitting behind him were gay, and afterward Sydnor talked to them. They hadn’t been to church in years.

“We talked about the unwelcome feeling they had felt in churches,” Sydnor said. “I came back [to St. George’s] and I said, ‘I think it’s time for us to be intentional about letting people of various sexual orientations know they’re welcome here.'”

Not long after, the parish agreed to add sexual orientation to its statement welcoming people to the church regardless of race, nationality or denomination.

“That was a grace-filled moment,” Sydnor said.

Sydnor credits St. George’s previous rector, Thomas Faulkner, with passing on a rich legacy of social activism, especially on matters of civil rights. Like Sydnor, Faulkner led the church for 30 years.

Under Sydnor, the church bought the property that became Hope House, a home for women and children. It helped start Building Bridges, which brings black and white worshippers together. And it provided seed money for the city’s first hospice.

As the church took its lead from Sydnor, the priest said he took his lead from Christ.

“He was always concerned about the little, the least, the last and the lost,” Sydnor said. “I really do believe he loves all of God’s children, and he loves them unconditionally.”

Guiding the church

As with any 30-year relationship, the one between Sydnor and his church had its joys and struggles.

Sydnor inspired people with powerful sermons that mixed Scripture with humor–and were blessedly succinct.

“He stops when it’s time to stop,” said longtime parishioner Brooke Snead, who bakes Sydnor a birthday cake every year.

He guided the church through a difficult stretch when a former treasurer confessed to embezzling thousands, then sought forgiveness.

He counseled parishioners through devastating personal losses and joyful celebrations.

“He took me through the death of my late wife of cancer, and through the marriage with my present wife,” Van Sant said. “I just think the world of him.”

But no church, and no minister, is immune to dispute.

Catherine Hicks, a St. George’s parishioner for 18 years, said she was at times maddened by Sydnor’s handling of internal church matters.

She said he hates conflict–which he also said–and his reluctance to confront it at times frustrated her and others.

But the rough times did not negate her respect for him.

“If I had to say, has he done a good job or has he done a bad job, he’s done a wonderful job,” Hicks said. “I certainly have fallen into the trap of wanting him to be more than human, to be perfect. Well, guess what? That’s an impossibility.”

In his final sermon and in a conversation a few days before, Sydnor talked about the inevitability of disagreements–and the importance of handling them respectfully.

“Every Sunday, when we’re singing a song you despise, can you take some joy from the fact that the person standing next to you loves it?” Sydnor said.

Fulfilling vows

When their cottage in his native Westmoreland County is renovated, Sydnor and his wife will move from their house in Fredericksburg.

He’d like to do some gardening, and the couple plan to take their grandsons to the zoo.

He will continue his work as an ecumenical officer for the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia.

But his focus will be on his wife.

“It’s what any husband would do to fulfill their marriage vow,” Sydnor said. “It is certainly what my wife, I’m quite sure, would be doing for me if the shoe was on the other foot.”